This content was published: January 2, 2023. Phone numbers, email addresses, and other information may have changed.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen’s New Alphabet

Posted by Christine Weber

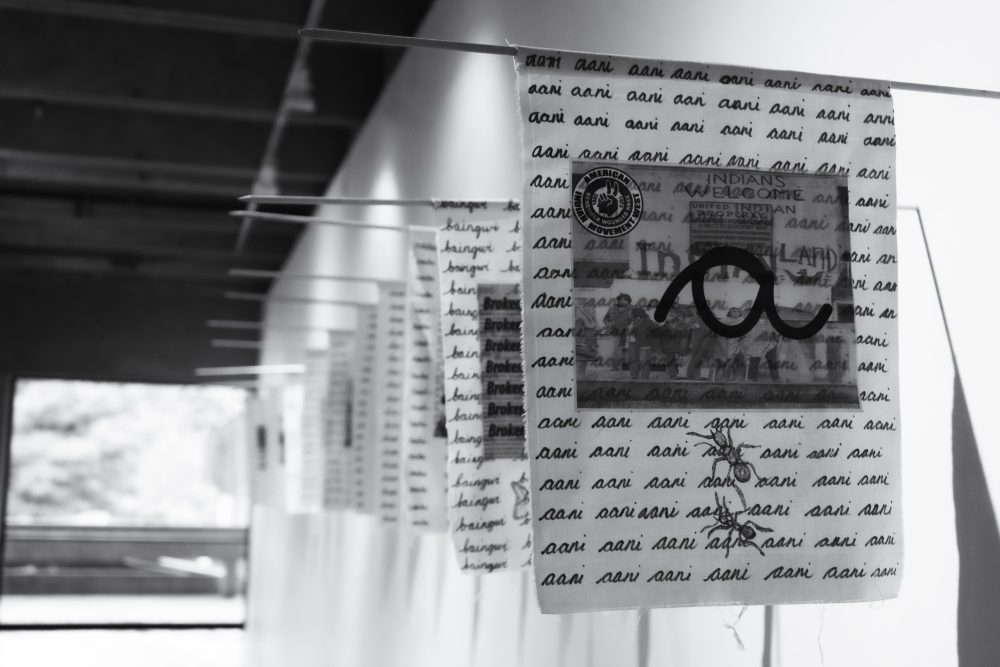

Wall of flags from Rochelle Kulei Nielsen’s exhibition, What Your White Mama Didn’t Teach You About Indians, 2022. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen – A New Alphabet

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen’s exhibition, What Your White Mama Didn’t Teach You About Indians (November 3 – December 14, 2022) engaged with the legacies of settler colonialism, recalling many hallmarks of early childhood education, a term often assumed to be beneficial or at least benign. Nielsen wrapped the gallery with chalkboards, penmanship lessons, and hovering children’s toys, creating a space for contemplating what we in the US have been taught about the Original Peoples of these lands and how much many of us still have to learn.

Installation view of “What Your White Mama Didn’t Teach You About Indians” in the North View Gallery. 2022. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

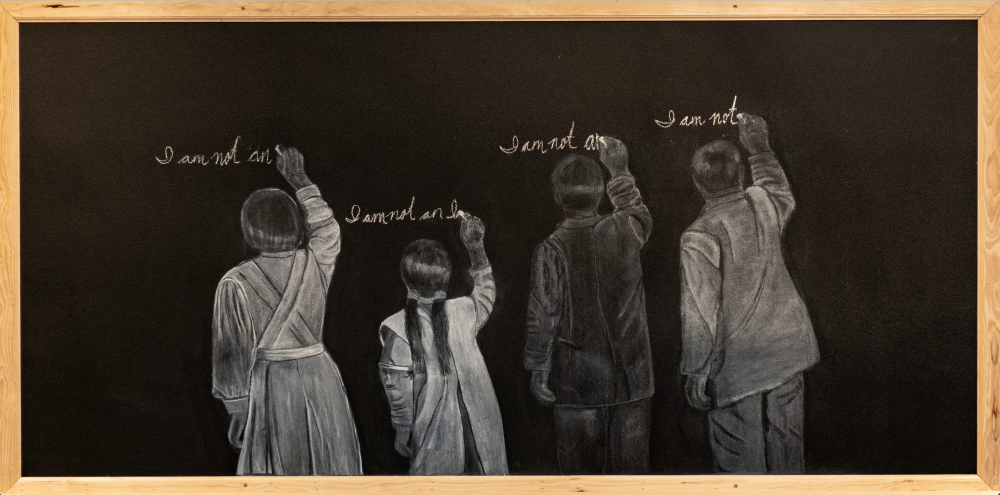

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “I am not an Indian”, chalk and chalkboard paint on board, 4′ x 8′. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

About the artist

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen is a member of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. She has served the Native community for the past 22 years, working as the Native American Education Coordinator in the Vancouver, Evergreen, and Battleground School Districts. She also served as the coordinator of the 10th Anniversary of the Northwest Indian Storytellers Association (NISA) Festival and Workshops with the Wisdom of the Elders, Inc. She has taught at Marylhurst University and Portland State University, where she was affiliated faculty with the Indigenous Nations Studies Program, teaching a course on Indigenous Critique of Native American Art. Currently, Rochelle maintains an active studio practice and teaches in both the Art and Native American Studies programs at Portland Community College.

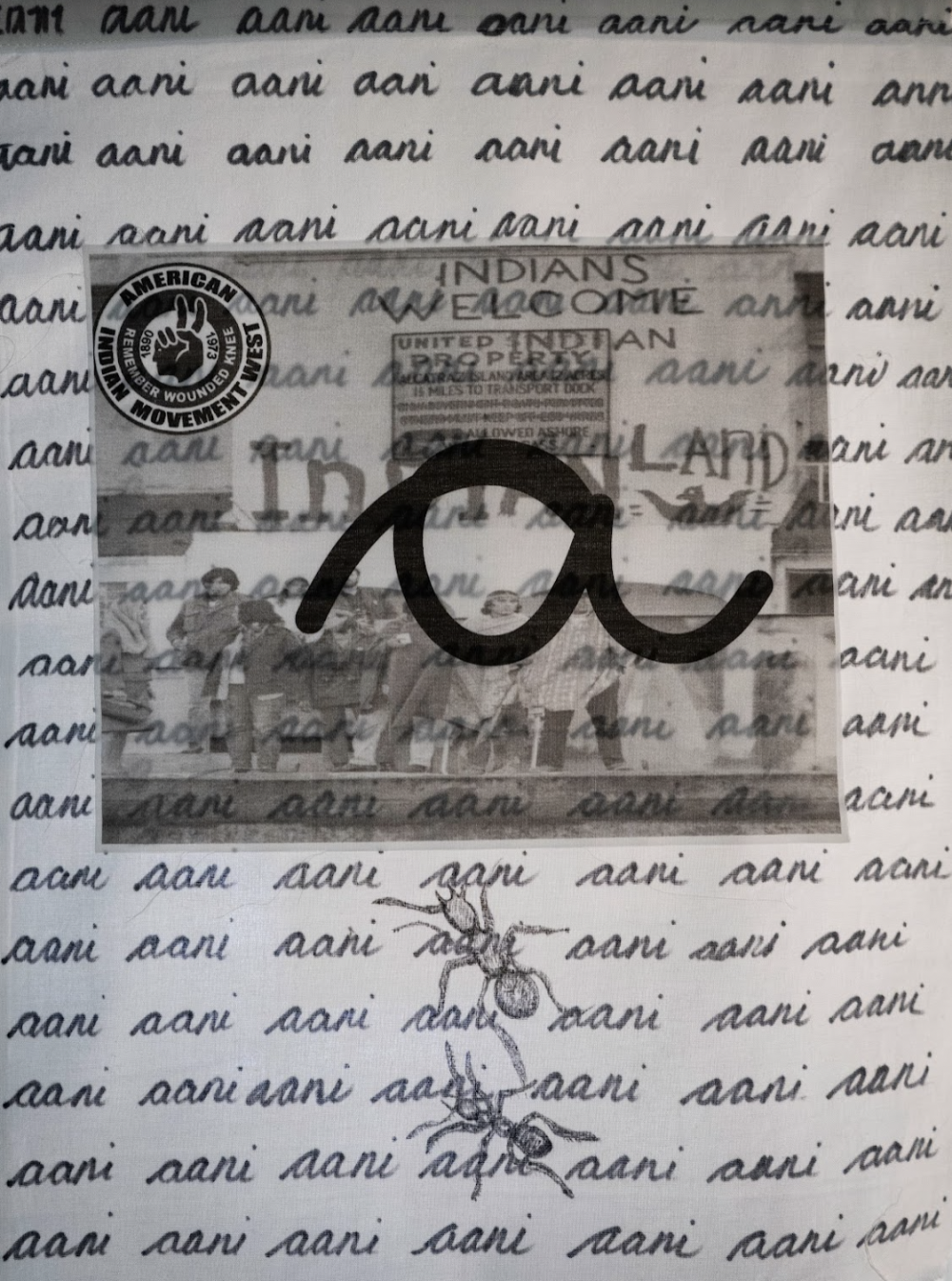

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “A is for A.I.M.” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

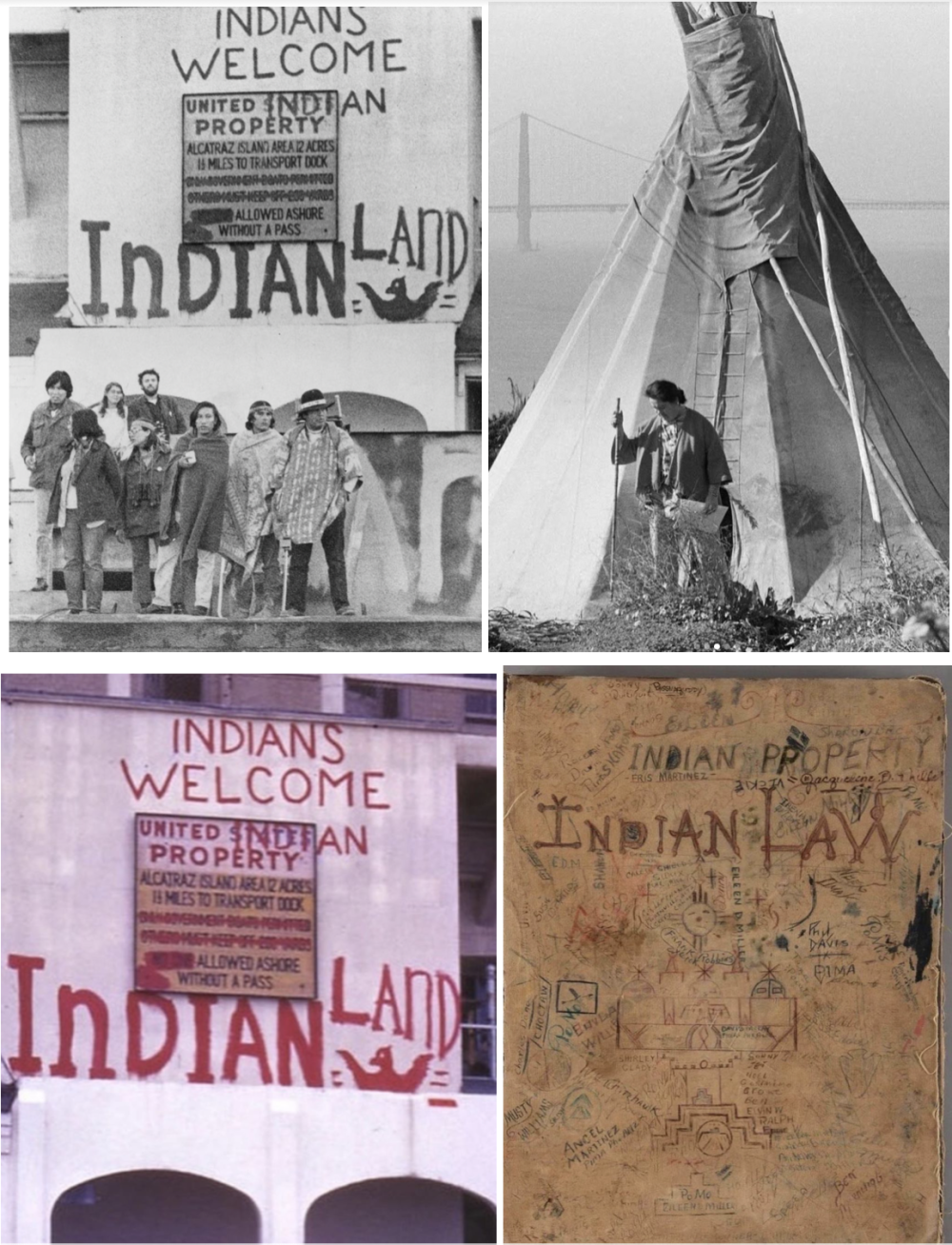

The first flag in this new alphabet honors the Occupation of Alcatraz Island that took place between November 20, 1969, and June 11, 1971. The occupation was organized by 78 Indigenous leaders and activists, including members of A.I.M. (the American Indian Movement) and Indians of All Nations. They demanded land back and the establishment of a Native American University. They organized quickly, electing a council, dividing up jobs, and forming a school on the island.

Everyone who arrived at Alcatraz (more than 3,000 people by the end) wrote their names, Tribal affiliations, and observations in an accounting ledger, which was recently scanned and is accessible online through the Autry Museum. This occupation that lasted for 19 months marks the first flag of Rochelle Kulei Nielsen’s alphabet. “A is for A.I.M.” proposes a new education that begins with Indigenous agency and strength.

Historical photographs from the Alcatraz occupation. Lower right: Cover of the accounting ledger in which over 3,000 people who arrived at Alcatraz wrote their names, Tribal affiliations, and observations. Source: The Autry Museum.

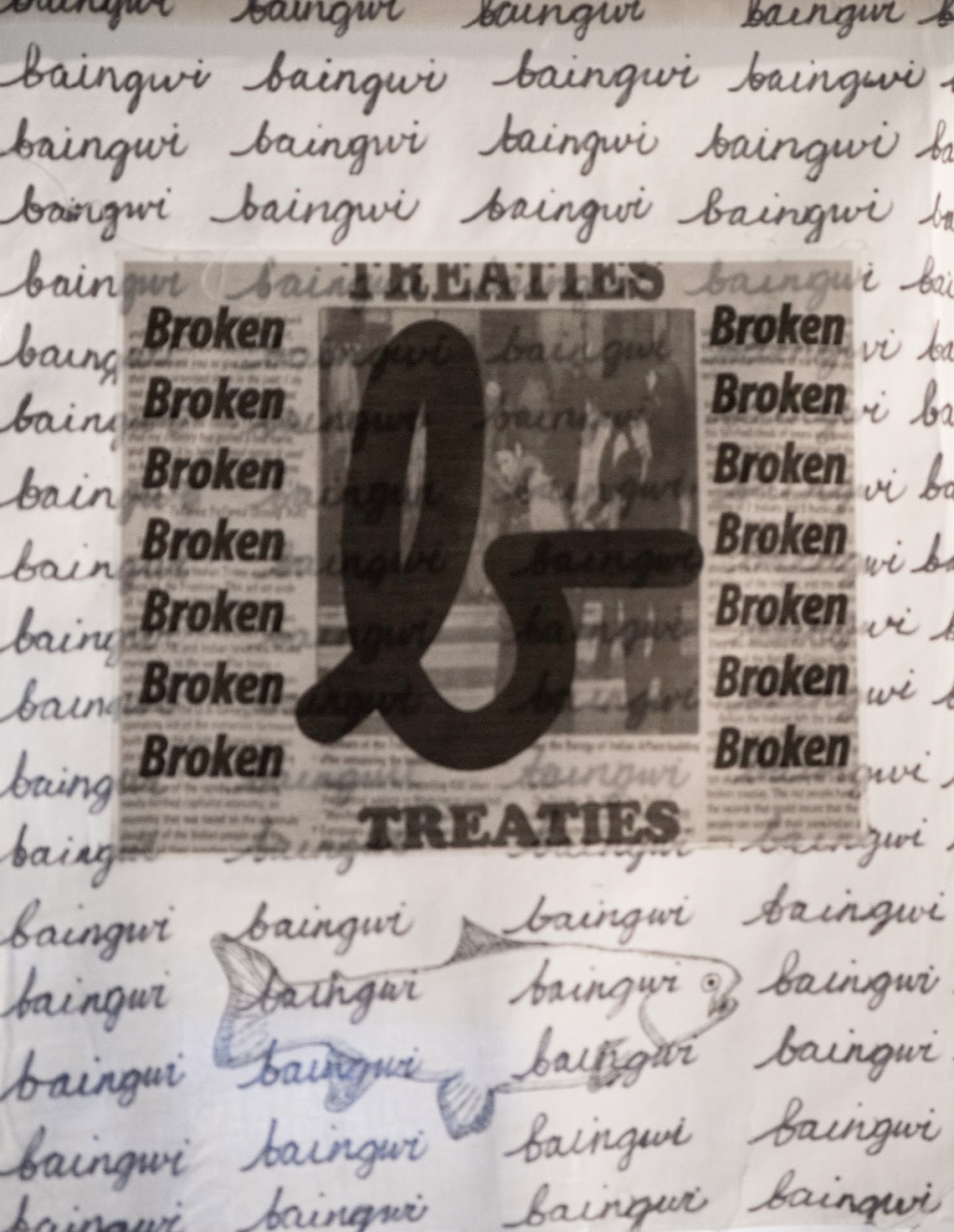

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “B is for Broken Treaties” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

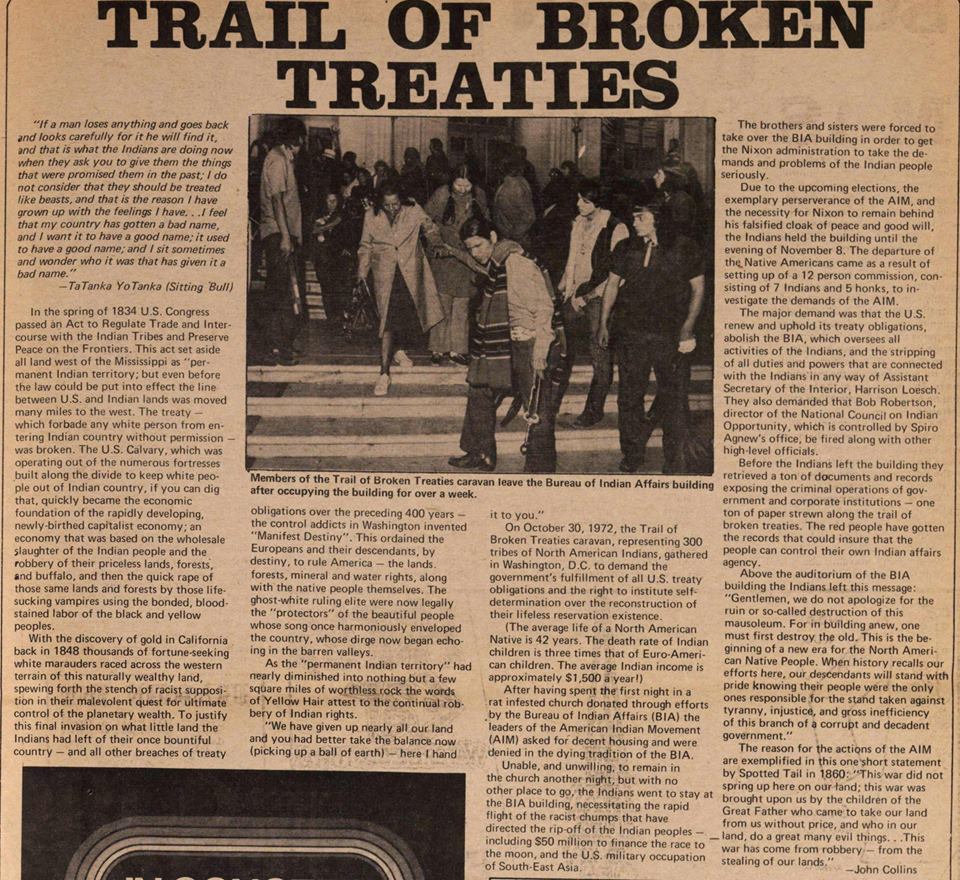

The second flag in Nielsen’s alphabet marks the day of November 3, 1972, when the Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan traveled to Washington DC, and occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) for six days. This group of more than 800 people, representing 300 Indigenous Nations also shared a 20 Point Position Paper demanding a more honest relationship with the US Government. They explained that in order for Indigenous communities to flourish, they needed improvements in health, housing, employment, and education that were self-determined. They also requested the protection of Indigenous religious freedom and their cultural integrity. While occupying the BIA offices, leaders found a vault full of tape recorders and cameras, and people began using them to interview each other and document the needs of the many Indigenous communities represented there.

Read the full 20-point Manifesto on the AIM (American Indian Movement) website.

Read the full account of Susan Shown Harjo’s experience of the occupation published in Indian Country Today.

The occupation on the cover of the Ann Arbor Sun, December 2, 1972.

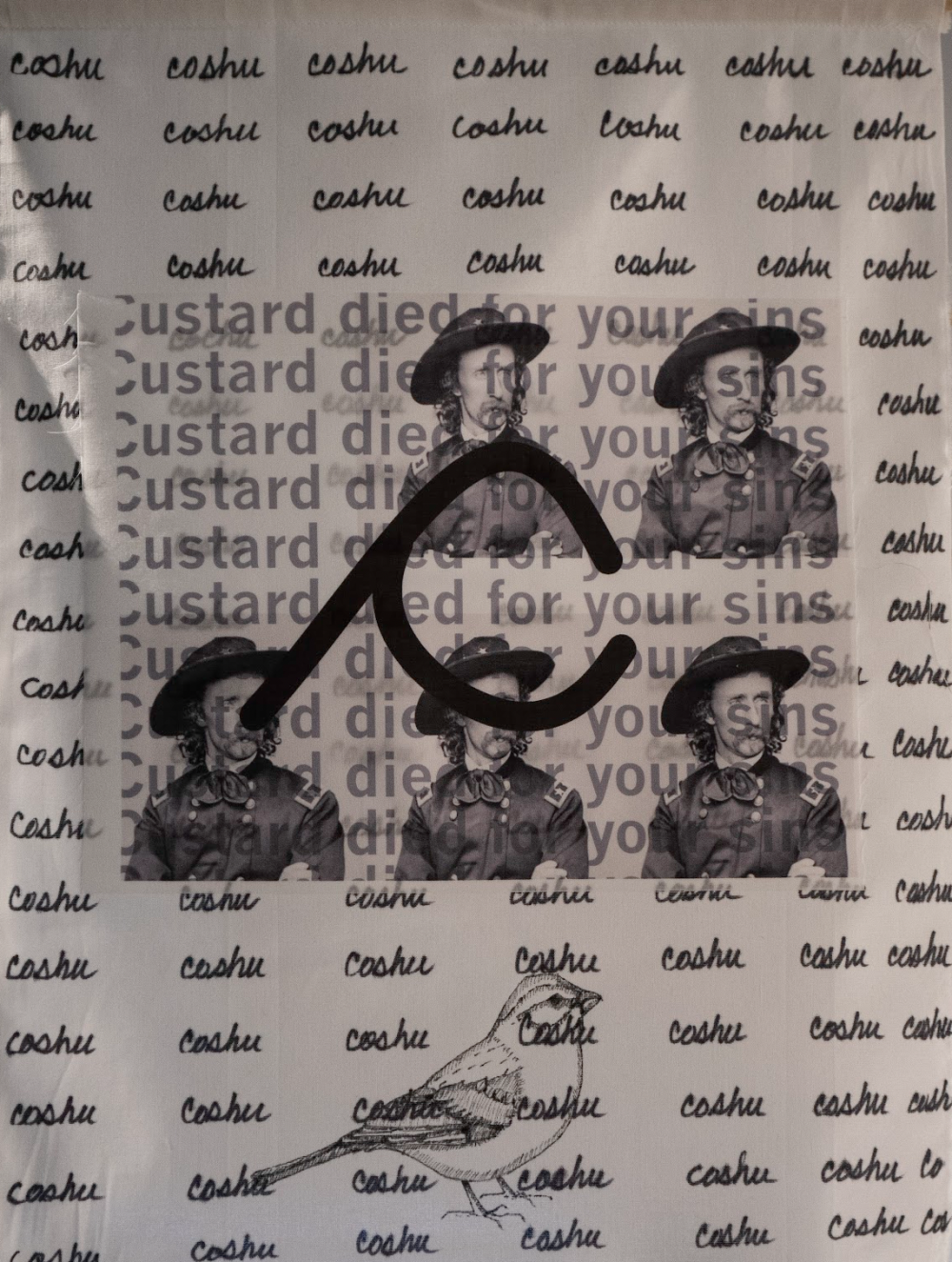

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “C is for Custard” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

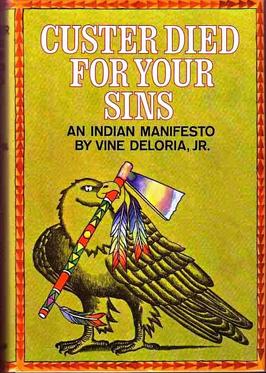

This flag references a significant book from the Red Power Movement. Custer Died for Your Sins, written in 1969 by Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux). The book is a collection of essays that call for Indigenous sovereignty, rejecting political and social assimilation. Throughout the book, Deloria is critical of aid organizations, including churches, which Deloria argues do more harm than good. He is also critical of disciplines like anthropology, ultimately causing anthropologists to reconsider their approach to working with Indigenous communities. Finally, Deloria explores the importance of Indian humor in the book, and Nielsen leans into that humor on this flag by referring to US Army Officer General George Custer as Custard, a European dessert or pastry filling. Custer was central to brutal treaty violations, specifically the US campaign to steal the Black Hills from the Lakota Sioux. Deloria’s book explains Custer’s violent treatment of Indigenous people and argues that US citizens should examine what they have learned about Western Expansion and Indigenous Treaties, challenging us all to acknowledge the brutality of US history.

Book cover of the first edition of Vine Deloria Jr.’s “Custer Died For Your Sins”, 1969.

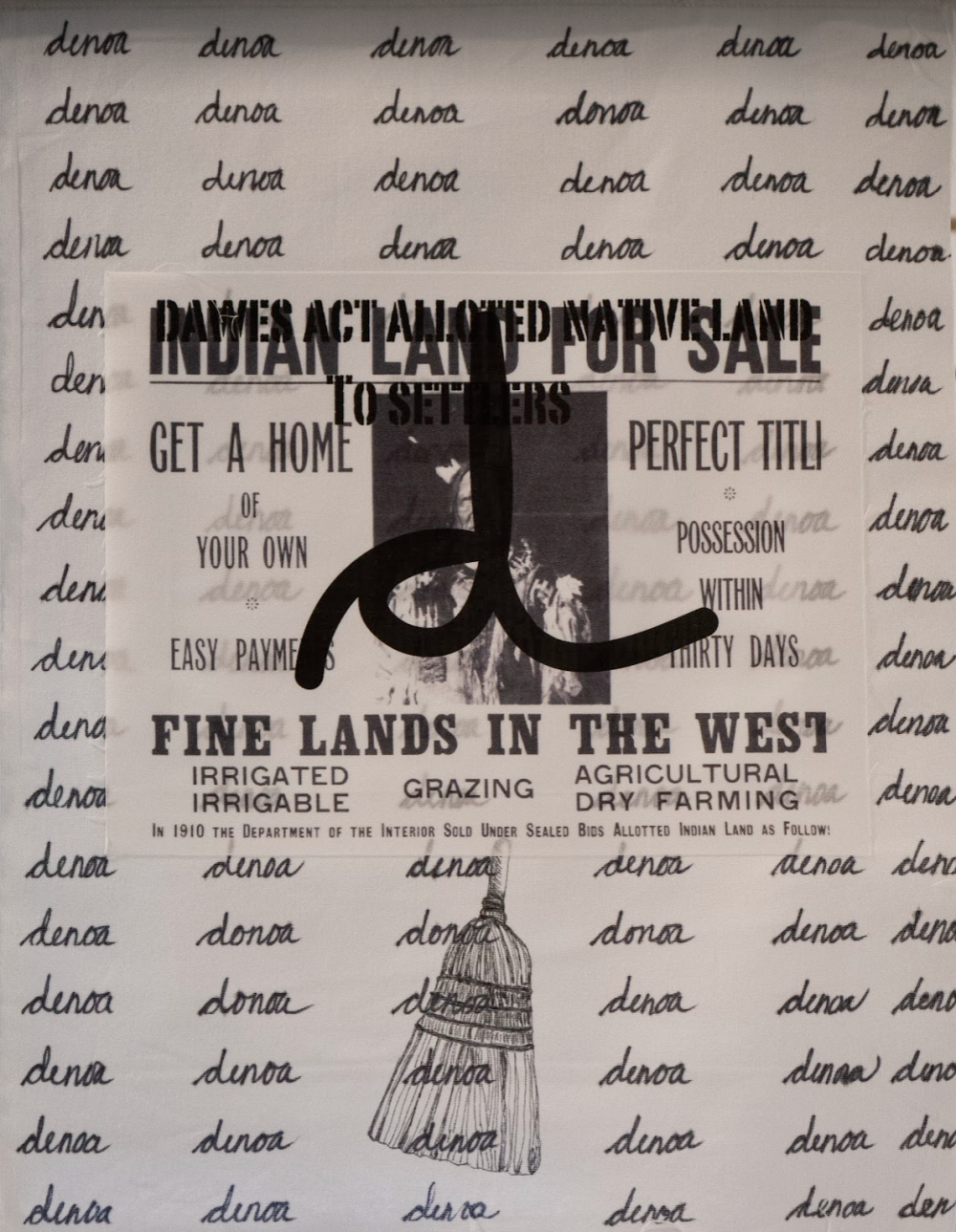

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “D is for Dawes Act” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

The Dawes Act (or the General Allotment Act) of 1887, subdivided lands held by Native nations in an attempt to force capitalist concepts like “private property” on Native peoples. One significant result of this act is that between 1887 and 1934 Native Americans lost control of over 100 million acres of land. This loss of land and the fracturing of traditional leadership structures that resulted cause historians like Sandy Grande to cite the Dawes Act as one of the most destructive US policies for Native Americans in history.

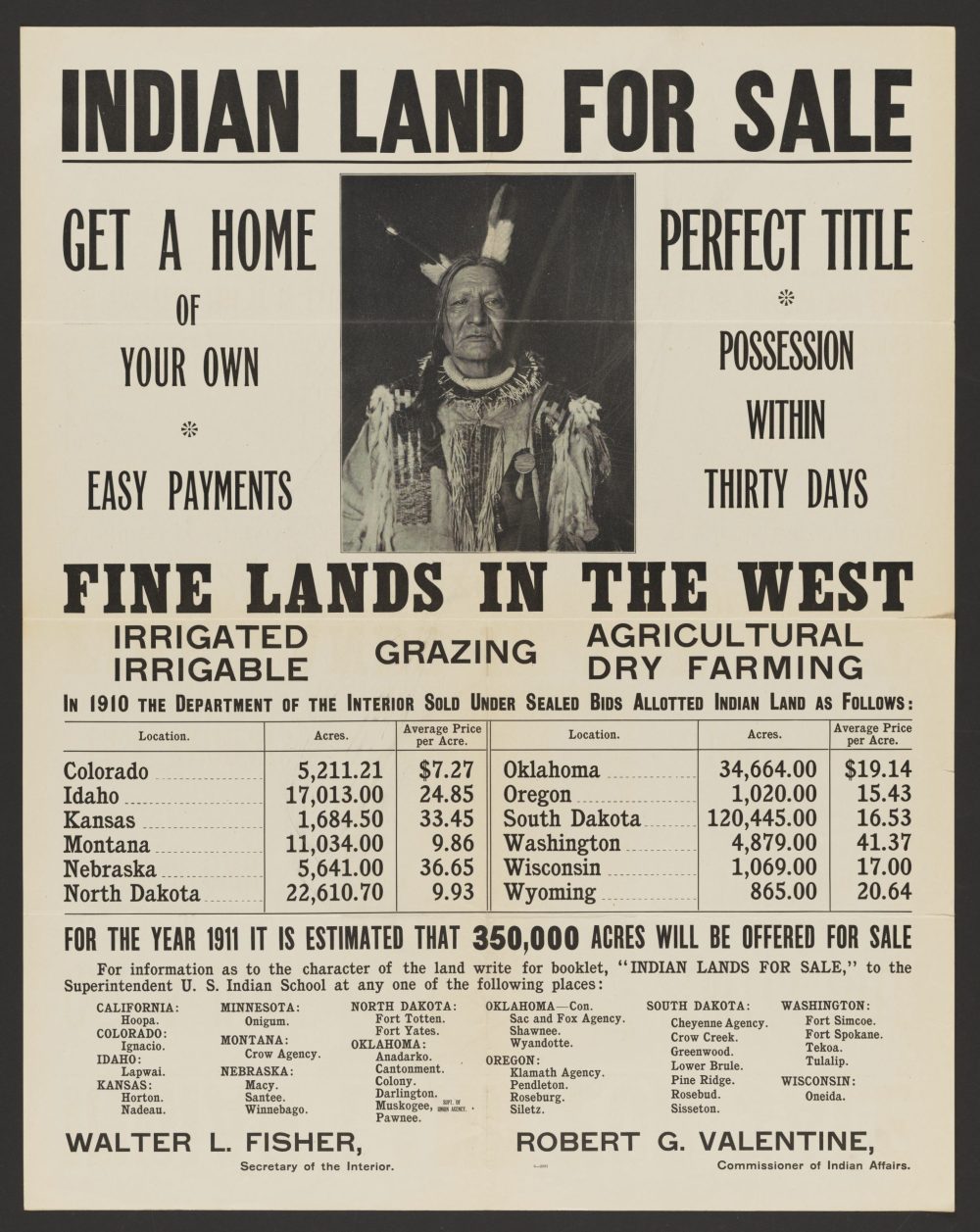

This flag also centers a broadside advertisement from the US Secretary of the Interior and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs offering “Indian Land For Sale” in 1911. The full-page ad explains how much land was sold the prior year in 1910 and explains that about 350,000 acres will be offered for sale in 1911, including land in Siletz, Roseburg, Pendelton, and the Klamath Agency of Oregon, along with sites across the western states. The man in the photograph is Padani-Kokipa-Sni (Not Afraid of Pawnee) of the Yankton Indian Nation.

Fisher, Walter L, et al. Indian land for sale: get a home of your own, easy payments. Perfect title. Possession within thirty days. Fine lands in the West. United States. Publisher not identified, 1911. Source: Library of Congress.

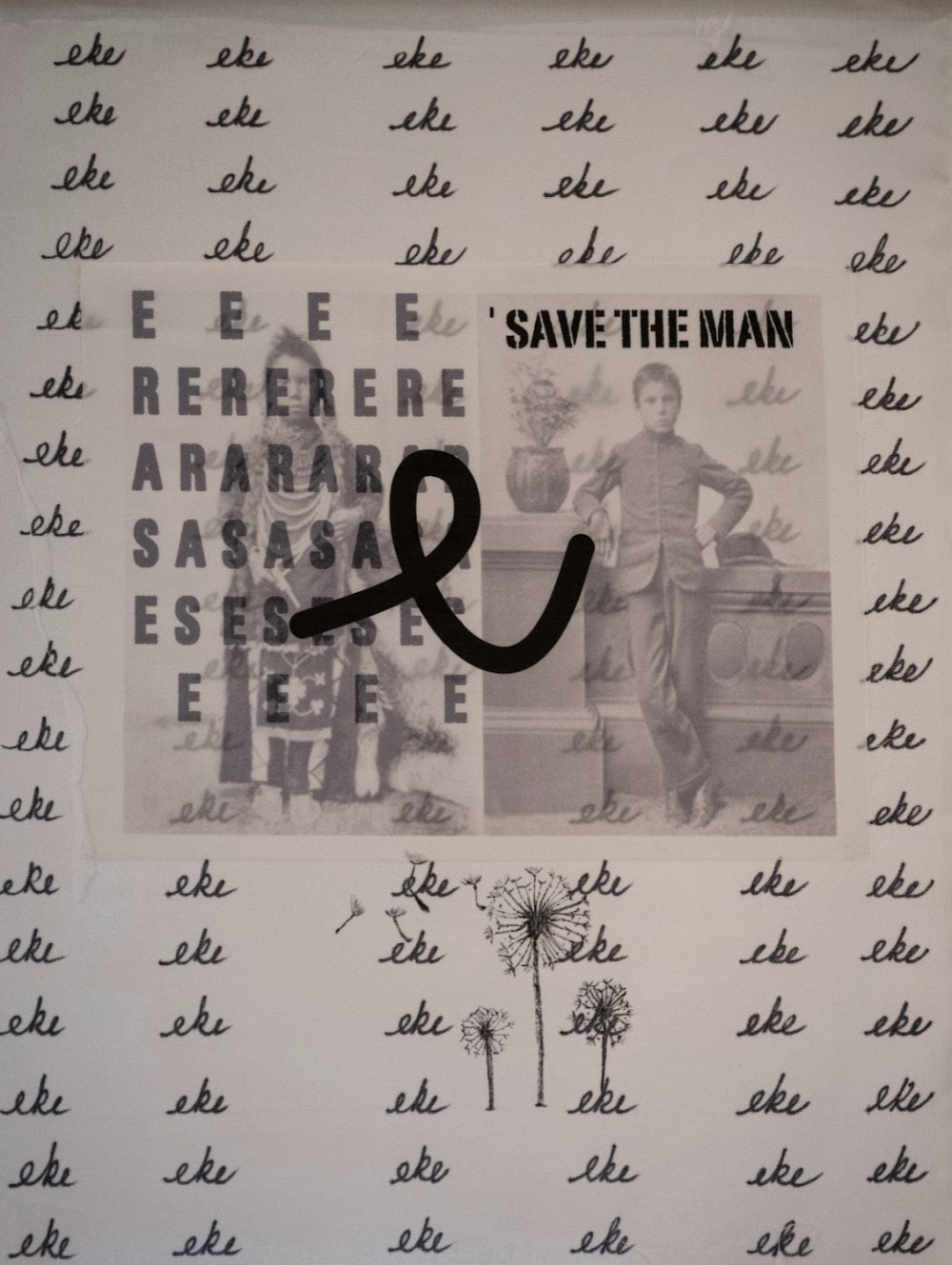

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “E is for Erase” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

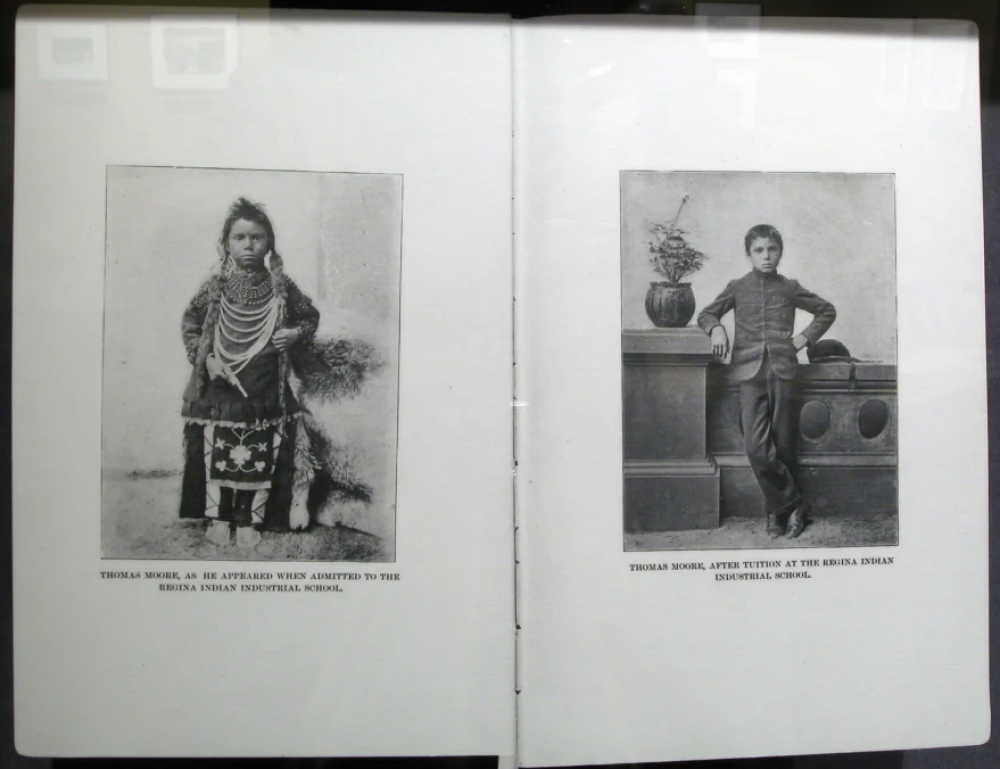

This flag honors two photographs of a young boy named Thomas Moore Keesick from the Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation. This photographic pair shows Keesick upon admission to the Regina Indian Industrial School in 1897 when he was 8 years old, and after school, leaders forced him to remove the clothing and long hair that connected him to his community. Images like this portrait pair serve as heartbreaking reminders of the history that Nielsen explains was not taught to most US citizens, by their family or by the education system. As Indigenous scholar Sandy Grande asserts, indoctrination through education was a vital component of the theft of Indigenous land, resources, and labor. Kulei Nielsen’s exhibition exposes the impact that settler schooling, in all of its forms, had on young people, while also considering the many ways that settler colonialism remains an oppressive force today.

Two photographs of Thomas Moore Keesick, published in the Canada Sessional Papers, No.14, Volume XXXI, No. 11 (1897), a Department of Indian Affairs Report for the year ending at June 30, 1896. Photograph: Naomi Angel.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “F is for First Nations” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “G is for Genocide” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “H is for Haskell Babies” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.This flag features a photograph of a group of Native American children at the Haskell Institute, taken between 1884 and 1889. The Haskell Institute was an Indian Boarding School established in Lawrence, Kansas in 1884. The boarding school was traumatic for Native children and their families. Students were required to stay at Haskell for four years without contact with family and tribes, to sever the connection to tribal traditions and customs. During the early years, the school was run like the military, requiring students to wear uniforms and march everywhere.

Group of Native American children at Haskell Institute, Lawrence, Kansas. One of the children, is holding a sign “Haskell Babies”. Photograph taken between 1880 and 1889. Source: Kansas Historical Society.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “I is for the Indian Religious Act” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

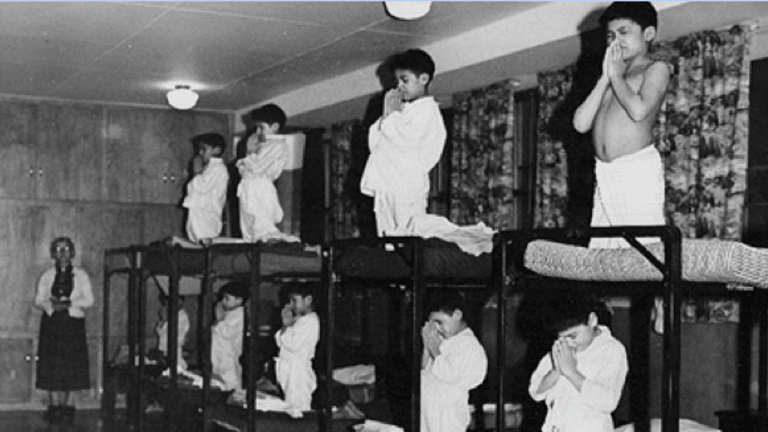

This flag features a photograph of residential school children in a typical dormitory, taken in 1950 at the Bishop Horden Memorial School. The Bishop Horden boarding school was a residential school in the Indigenous Cree community of Moose Factory, Ontario Canada. In this school and many others, Indigenous children were forced to pray at the foot of their mattresses prior to being permitted to sleep, in this photograph, they are watched by a Catholic Nun acting as disciplinarian and enforcer. Forced conversion to Christianity was one of many ways that the religious freedoms of Indigenous peoples were denied by settler governments.

In the United States, Native American religious practices have been historically prohibited by federal laws and policies. For example, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 that resulted in the forced relocation of hundreds of Native nations from their land also impacted Indigenous religious freedom. Not only were Native peoples forcibly assimilated into agricultural settler societies far away from their original lands, but the relocations left them without access to the sacred sites where they had traditionally practiced their beliefs. In fact, many Indigenous spiritual ceremonies are impossible to practice without access to a specific site because place is an important component of Indigenous spiritualities. Indigenous people have also been banned from using sacred ceremonial items that were restricted under US law. Finally, the indoctrination that took place at Indian Boarding Schools furthered the infringement upon Indigenous religious freedom.

In 1978, US Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which acknowledged that the US government had denied Indigenous people their First Amendment right to the “free exercise” of religion.

Photograph of residential school children in a typical dormitory, taken in 1950 at the Bishop Horden Memorial School. Source: CNS photo/Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre, Handout via Reuters.

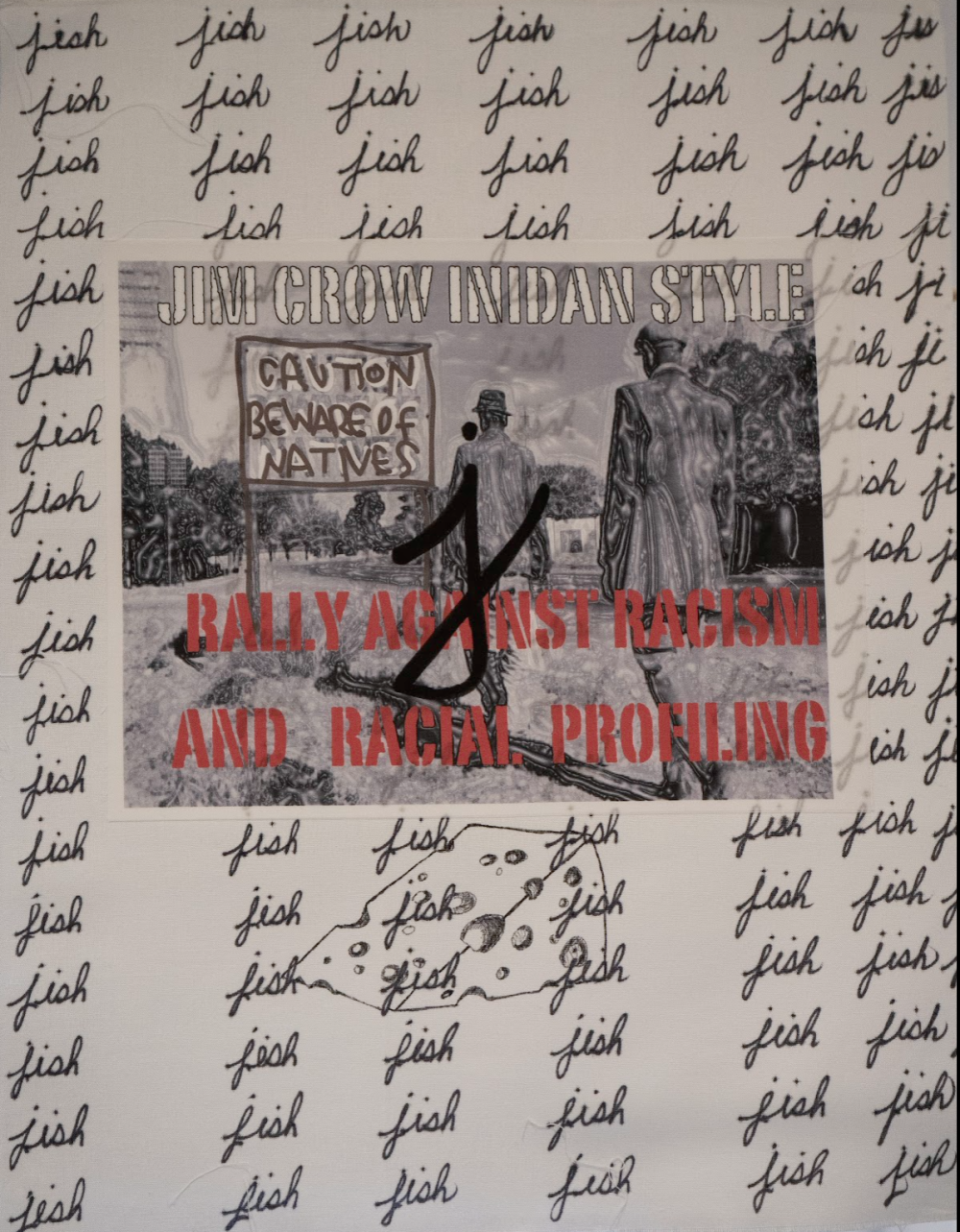

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “J is for Jim Crow Indian Style” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

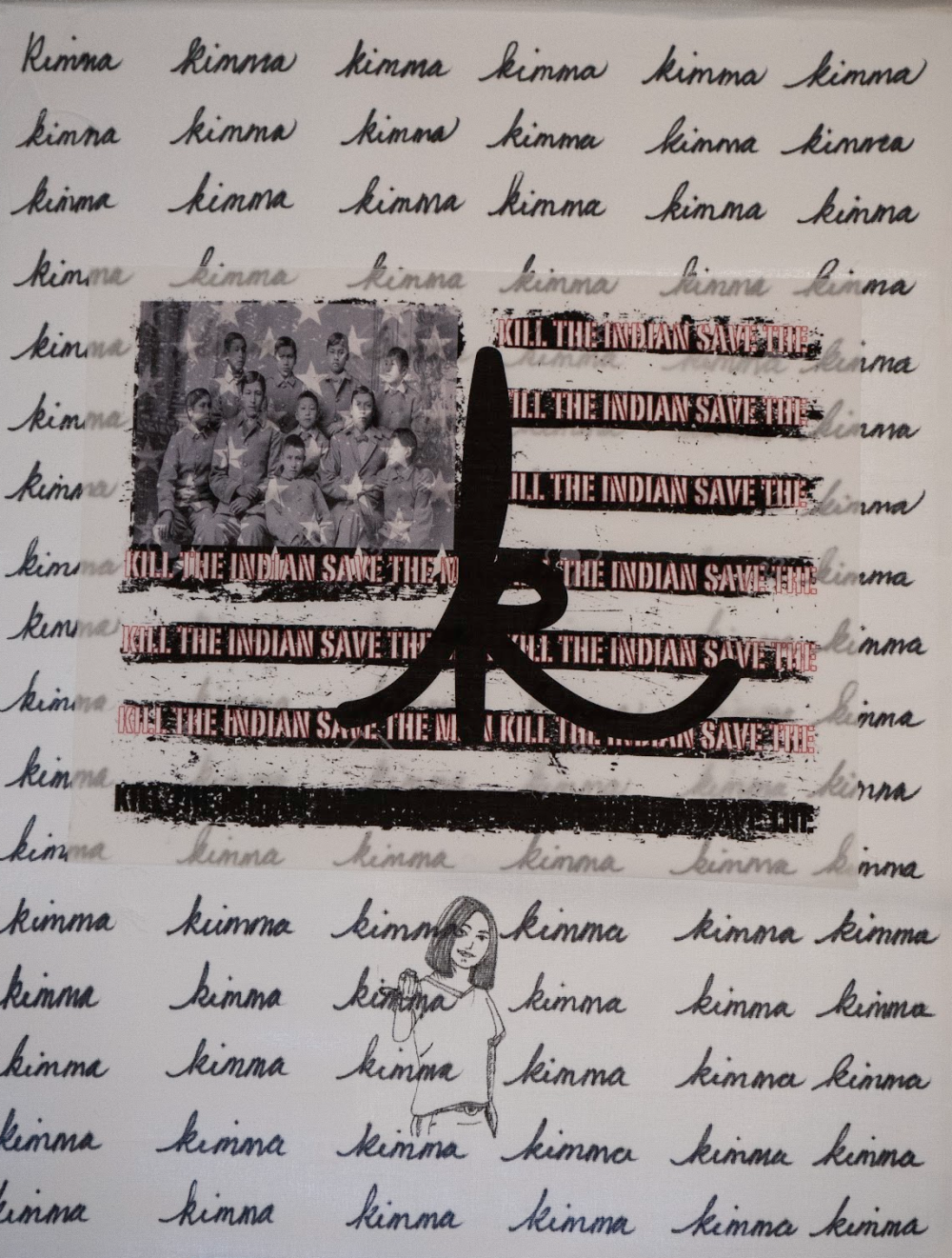

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “K is for Kill the Indian” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

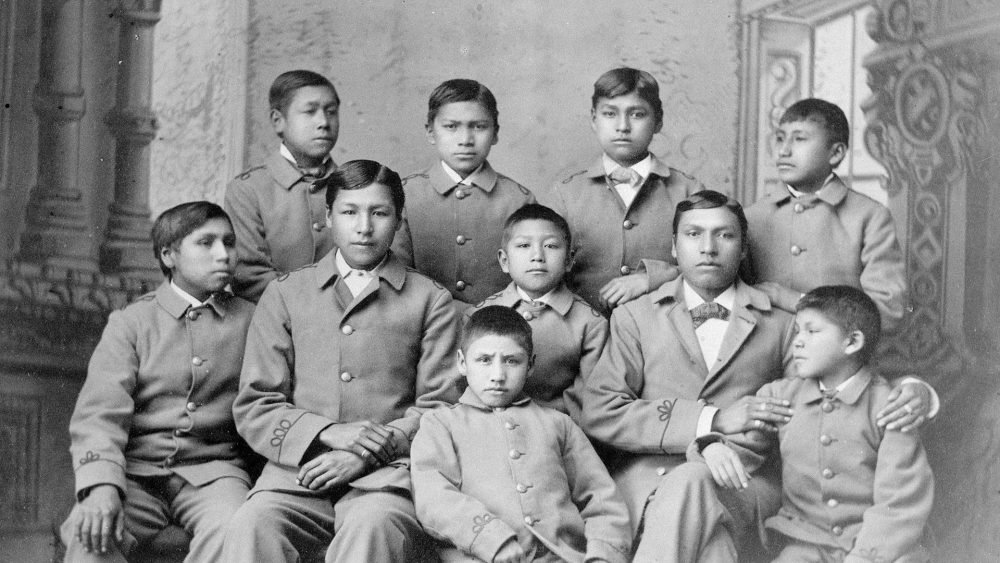

A photograph of a group of students in cadet uniforms at the Omaha Nation at Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania is contained by the stars of the US flag that hovers over this Shoshone flag. The photograph was taken shortly after 1879 when the U.S. government launched a policy of forcibly removing Native children from their families and tribal communities and placing them in residential boarding schools far from their homelands and cultural contracts. These militaristic schools expressly forbid children from contacting relatives and forced the adoption of Christianity, the English language, and Euro-American customs, values, and practices.

The goal of the boarding schools is the complete eradication of Native identity, culture, and values and the adoption of White / Euro-American, Christian, and heteropatriarchal values. Capt. Richard H. Pratt established the primary model for all off-reservation boarding schools with the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Pratt’s motto was “Kill the Indian, save the man,” and this encompassed eradicating any signs of Native life and practices, including cutting the hair and braids of Indian children, forbidding Indian languages or customs, forcing Christianity and Christian dogma and practices, and forbidding hugging, even among siblings.

Children were required to wear militaristic-style uniforms and adopt new English-language names and surnames. In many of the boarding schools, children were severely punished or tortured if caught violating any of the cultural rules and, in some cases, murdered. Parents who refused to send their children were imprisoned. By 1880, there were more than 7,000 Indian children enrolled in federally supported missionary-run boarding schools.

(From the introduction to the special issue of the Journal of American Indian Education, “Native American Boarding School Stories” by K. Tsianina Lomawaima 2018)

Photograph of a group of students in cadet uniforms at the Omaha Nation at Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, c.1880. Source: Bettmann Archive.

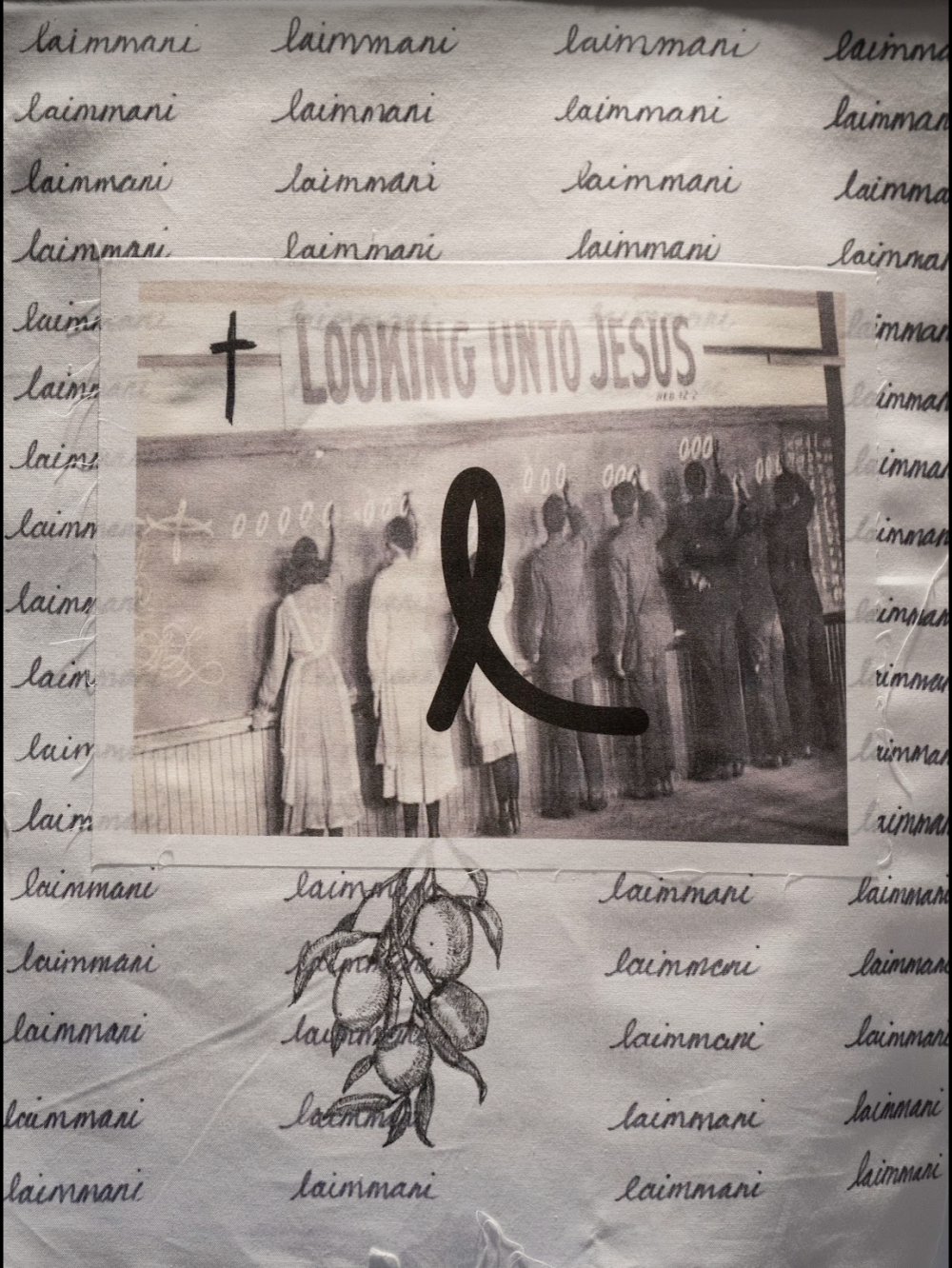

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “L is for Looking Unto Jesus” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

The students in a penmanship class at the Red Deer Indian Industrial School are honored on this flag. They were photographed sometime between 1914 and 1919, more than thirty years after the Indian Affairs Commissioner J.D.C. Atkins banned Native languages in schools. After 1887, all mission and government-run schools on reservations were required to provide English-only instruction.

Nielsen’s installation considered the many cultural practices and languages, including the artist’s own Shoshone language, that US colonizers tried unsuccessfully to erase. She further exposed the violence of public education by creating a space for viewers to reenact the experience of her mother, who after being caught speaking Shoshone in school, was forced to write “I’m not an Indian” on the chalkboard multiple times. What does it feel like to be forced to deny an important part of one’s identity, multiple times and in front of peers? What does it feel like to be told that who you are is wrong? Nielsen asked viewers to consider the relationship between schooling and settler violence. Why was it so important for the oppressors that Indigenous nations stop using their own languages? In what overt and covert ways does education today still uphold white heteronormative capitalist patriarchy? What happens when significant parts of US history are no longer hidden but are openly and honestly discussed?

Photograph of a penmanship class at the Red Deer Indian Industrial School, in Red Deer, Alberta, Canada, c.1914 or 1919. Source: United Church of Canada Archives.

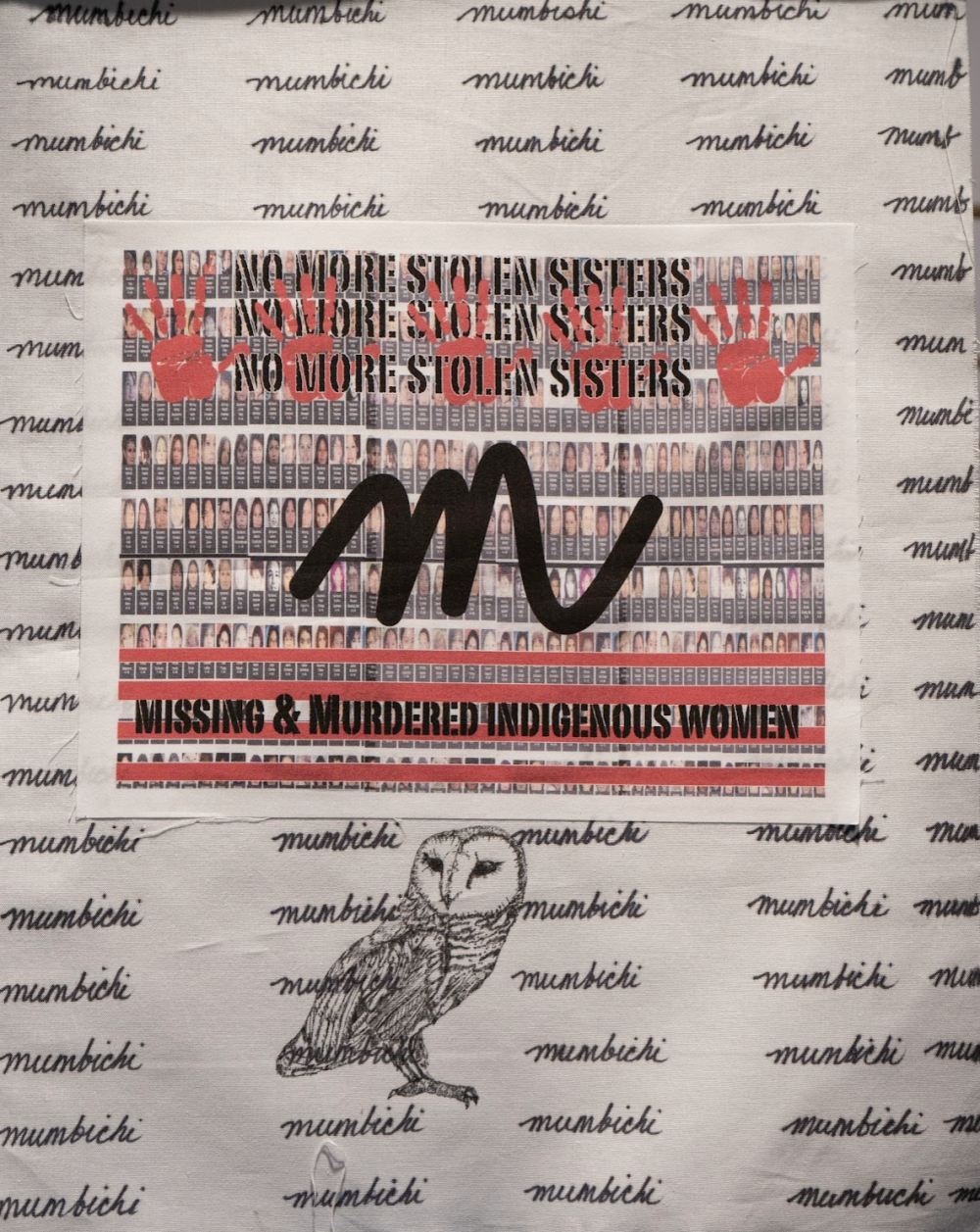

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “M is for Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

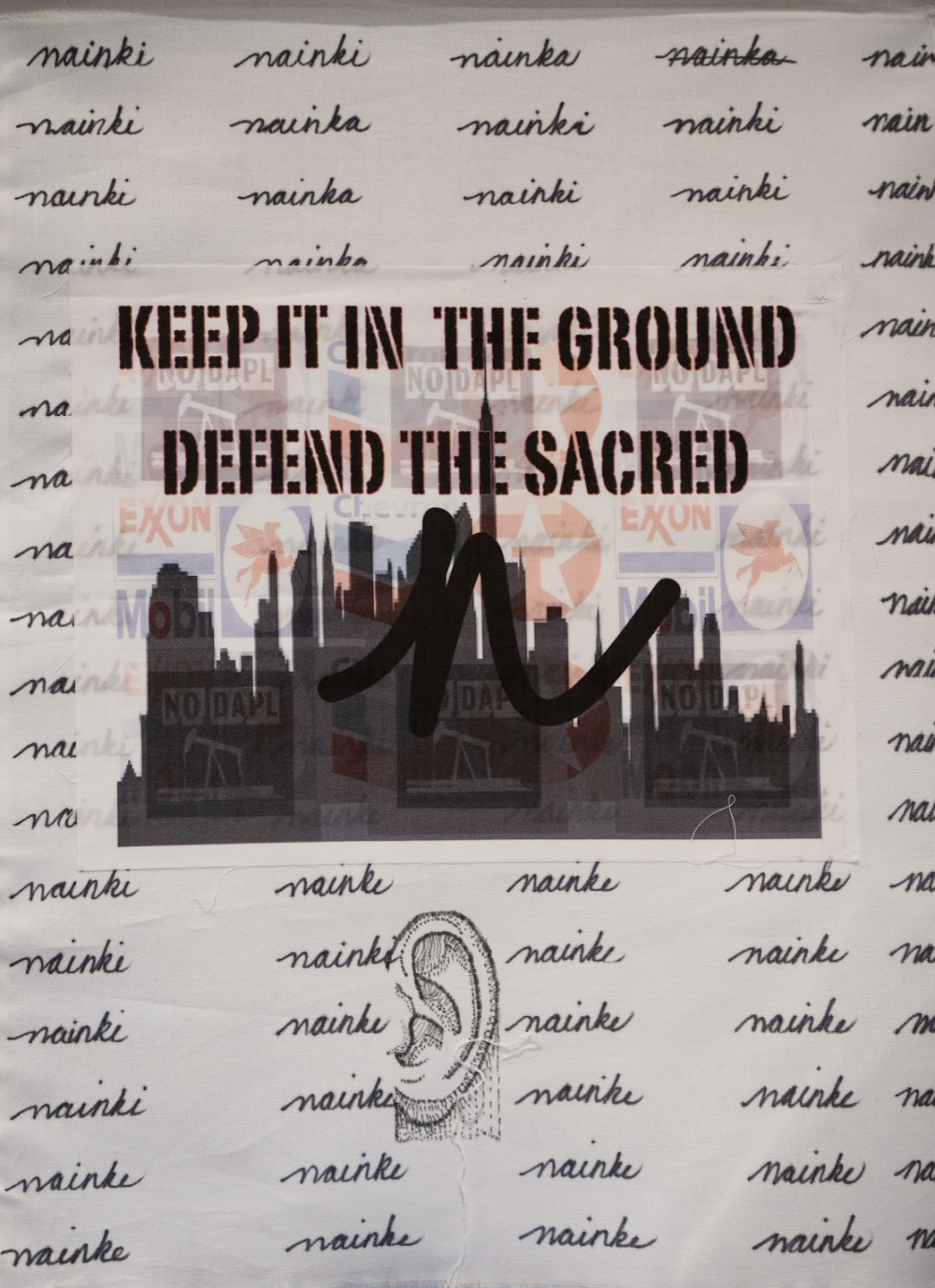

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “N is for No DAPL” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “O is for Oil” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “P is for Protectors of the Land” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “Q is for Blood Quantum” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “R is for Reservations” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “S is for Survive” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “T is for Trail of Tears” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “U is for Untoke” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “V is for Voting” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “W is for the Indian Child Welfare Act” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Studio photograph of four girls who are dressed with fully beaded yokes, moccasins and leggings in the style characteristic of Lakota and Cheyenne beadwork of the early reservation period. South Dakota, c.1890. Source: Vincent Mercaldo Collection.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “X” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “Y is for Y-DNA” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Rochelle Kulei Nielsen, “Z is for Zimee” digital print and drawing on cloth, 2021. Photograph: Jordan VanSise.

Selected bibliography

Grande, Sandy (Quechua). Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought, 10th Anniversary Edition. Rowman & Littlefield. 2015.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma). “Native American Boarding School Stories” special issue of the Journal of American Indian Education. 2018.

Reed, Britt (Choctaw). “Indian Child Welfare Act: Historical and Legal Context”, The Last Real Indians. August 16, 2015.

van Thater-Braan, Rose (Tuscarora-Cherokee). “The Six Directions: A Pattern for Understanding Native American Educational Values, Diversity and the Need for Cognitive Pluralism.” SECME Summer Institute plenary session. July 10, 2001.

NYC Stands with Standing Rock Collective. 2016. “#StandingRockSyllabus.” nycstandswithstandingrock.wordpress.com/standingrocksyllabus/.